The ruling African National Congress (ANC) was dealt an historic blow in last week’s general election, losing its majority for the first time since South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994.

The economic and social crisis that has been developing in South Africa is now being expressed on the political plane, with a period of unstable coalitions and open splits in the ruling class on the order of the day.

ANC humiliated

This result represents first and foremost a damning indictment of the ANC, which has been in power for 30 years. It won only 40 percent of the vote, down from 62 percent in 2019, and much lower than expected. In truth, the seeds for this collapse were sown by the historic class compromise made by the ANC leaders during the fall of Apartheid.

From the 1940s onwards, the ANC became recognised as the leader of the anti-Apartheid struggle. When the mass revolutionary movement of the workers and youth erupted in the 1980s the ANC placed itself at its head, uniting with the South African Communist Party and the Confederation of South African Trades Unions (‘Cosatu’) to form the ‘Tripartite Alliance’.

Therefore, when the ruling National Party turned from naked repression to negotiations as a means of preventing the revolution from going ‘too far’, the ANC naturally took the lead in representing the liberation movement in these negotiations.

At this time, the programme of the ANC was officially the ‘Freedom Charter’, which combined democratic demands, such as universal suffrage, with radical social demands, including the nationalisation of the land, the mines, the banks and industrial monopolies. For the working-class rank-and-file of the Tripartite Alliance, this meant nothing short of socialist revolution. However, while the ANC had the active support of a large section of the South African workers and youth, its leadership retained at all times a middle-class, reformist outlook.

In the course of these negotiations, the ANC effectively traded in the socialist elements of its program for the political custodianship of the country on behalf of the capitalists. In a number of ‘Sunset Clauses’ it agreed, along with its ‘Communist’ partners in the SACP, not to touch the property of the white capitalists when in power.

Following this compromise with the South African capitalists and foreign imperialism, the ANC under Nelson Mandela won an overwhelming majority in the first democratic elections in April 1994. Millions of black South Africans voted the ANC into power, as their party, the party that ended Apartheid, which promised to deliver a transformation of their conditions of life.

Today, the results of this class compromise have never been clearer. South Africa is the strongest economy in Africa, but it has never truly recovered from the 2008 crash. GDP per capita is lower now than in 2009. Unemployment has risen to nearly 35 percent, transport and energy infrastructure is crumbling, and high inflation is eating into the workers’ wages.

Income inequality has in fact increased since the ANC came to power. With a Gini coefficient of around 0.67, South Africa is classed as the most unequal country on the planet. According to World Population Review: “The top 1 percent of earners take home almost 20 percent of income and the top 10 percent take home 65 percent. That means that 90 percent of South African earners take home only 35 percent of all income.”

White people are still more likely to find work (and work that pays better) than black people; women earn about 30 percent less than men; and urban workers earn roughly double that of those in the countryside. The government has been unable to offer any solutions to the intense cost of living crisis faced not only by the working class, but even parts of the middle class.

Consequently, both the ANC’s vote share and voter turnout overall have declined markedly since their peak in 1999, when the ANC won 70 percent of the vote with a turnout of 90 percent. And it is plain to see that it will never be able to rule as it had done in the past.

Splits at the top

The main beneficiary of the ANC’s decline has been the uMkonto we Sizwe party, led by disgraced former president, the 82-year-old Jacob Zuma / Image: World Economic Forum, Wikimedia Commons

The main beneficiary of the ANC’s decline has been the uMkonto we Sizwe party, led by disgraced former president, the 82-year-old Jacob Zuma / Image: World Economic Forum, Wikimedia Commons

At the same time, the widespread rejection of the ANC has not led to an increase in support for the official, bourgeois opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA). The DA received 21.8 percent of the vote this time around, having won 22.2 percent in 2019. This shows that there is no appetite whatsoever for the right-wing policies of privatisation, austerity and support for US imperialism, espoused by the DA and its leaders.

The main beneficiary of the ANC’s decline has been the uMkonto we Sizwe (MK) party, meaning ‘Spear of the Nation’ in Zulu, which is led by disgraced former president, the 82-year-old Jacob Zuma. The meteoric rise of this party, which was only founded last December, reflects an extremely bitter divide within the South African ruling class itself.

The programme of the ANC over the last 30 years can be summed up in three words: Black Economic Empowerment. But this has not meant any empowerment for the black working class. Intead, the ANC has striven to build up a black bourgeoisie in the country by placing black South Africans in top positions in the state and on the boards of major South African companies.

However, the commanding heights of the economy remain in the hands of white or foreign-owned monopolies. 39 percent of the companies listed on the Johannesburg stock exchange are classed as black-owned, but the major mining companies and industrial monopolies remain under the control of the white bourgeoisie and foreign imperialism.

Lacking sufficient capital to compete with these gigantic firms, a large section of the black bourgeoisie can find no other source of profits than through the looting of the state, in particular through government contracts.

This struggle over the capitalist pie has been expressed within the ANC for decades. In 2008, the incumbent president, Thabo Mbeki, was ousted by a rebellion within the ANC itself, which eventually placed Jacob Zuma in power, as the leader of this ‘radical’ faction.

Zuma is a member of the old guard of the ANC and had been a leading figure in its armed wing, uMkonto we Sizwe. But under his presidency it soon became clear that his ‘radicalism’ had nothing to do with the socialist aspirations of the South African workers. Rather, he gave leadership to a section of the black bourgeoisie that felt shut out of the profit making going on at the top, and resented the ‘responsible’ bourgeois politicians and black businessmen, who had obtained a seat at the big boys’ table, only to toss them the occasional scrap. “It’s our turn to eat”, was their motto.

What followed under Zuma was a carnival of corruption, which has often been referred to as ‘state capture’. The term ‘tenderpreneur’ became part of the South African vocabulary, meaning someone who makes money out of public contracts by exploiting their contacts in the ruling party, often in return for favours of various kinds, and not always legal ones.

After years of scandal, decline and disillusionment, Zuma was eventually deposed by the ‘moderate’ wing (meaning, the representatives of big capital within the ANC), and replaced by Cyril Ramaphosa, one of South Africa’s richest men, who had sat on the boards of several major companies.

While out of power, Zuma was charged for corruption and even sent to prison in July 2021 for contempt of court, having failed to appear before a commission of inquiry into state capture under his presidency. After Zuma’s imprisonment provoked riots in KZN, which led to the deaths of 300 people, Zuma was released on “medical grounds” only two months later.

In August 2023, the Justice Minister confirmed that Zuma would not have to return to prison “to ease overcrowding”, but his corruption charges are still hanging in mid-air, and he is still due to face trial. It is likely that Zuma had this in mind when, only a few months later, he launched his new party to take advantage of the crisis in the ANC and the discontent that was building up against it.

Ramaphosa had promised to clean up South African politics, but nothing has changed in the seven years he has been in power. The reason for this is simple: he cannot touch the property of the monopolies, who quite literally pay his wages, and he cannot attack the tenderpreneurs and corrupt profiteers because they make up the core of his party. The South African media often talks about Ramaphosa’s ‘collaborative’ approach and willingness to compromise, but in truth he can do nothing else. And all the while, conditions have continued to worsen for the South African masses.

Now this split in the ruling class has broken out into the open on a scale never seen before. The fact that Zuma’s party won 15 percent of the vote and is now the biggest party in Zuma’s home province Kwazulu-Natal (KZN) reflects the fact that it has the active support of a wide network of black capitalists, state functionaries and rural chiefs.

Zuma has his own motives, not least to preserve his freedom, but there are many in MK and even within the ANC itself who would like to use MK as a battering ram to depose Ramaphosa and shift the balance in the government back towards the ‘radical’ wing of the ANC.

But Zuma’s support extends beyond the black bourgeoisie and the tribal chiefs. It is clear that a section of the impoverished population in KZN is currently looking to Zuma to improve its conditions. As one unemployed youth put it, “What makes me put my hope in the MK is that I know that Zuma is able to fight for us in a lot of things, for us Black people.”

Zuma has demagogically latched on to the mass discontent that has been building up against Ramaphosa and the ANC, pointedly naming his party after the ANC’s armed wing, and combining slogans calling for the nationalisation of the land without compensation with calls for greater powers of traditional chiefs, protectionist measures and xenophobic immigration controls. He has also played on Zulu nationalism in KZN.

After years of crisis, and with no alternative being presented in mainstream politics, a small layer has turned towards nationalism and xenophobia, as has been seen in many other countries. Businesses owned by foreign nationals have been raided. Immigrants have been violently attacked and even killed. Only a bold socialist programme can cut across this mood, which is an expression of the dead end of South African capitalism.

EFF disappointed

Besides the ANC, the Economic Freedom Fighters, led by Julius Malema, will be disappointed with the results of this election. The EFF first emerged as a left-wing split from the ANC’s youth wing, and was founded as an official party in 2013, in the wake of the massacre of 34 miners by police at Marikana in 2012, an atrocity that both Zuma and Ramaphosa supported.

On the basis of its left-wing programme and radical language, the EFF has succeeded in drawing in a significant layer of the youth, and roughly a year ago they celebrated the 10th anniversary of their foundation at a rally of over 100,000 people in the FNB stadium in Soweto.

The Economic Freedom Fighters, led by Julius Malema, will be disappointed with the results of this election / Image: Julius Sello Malema, Twitter

The Economic Freedom Fighters, led by Julius Malema, will be disappointed with the results of this election / Image: Julius Sello Malema, Twitter

Polling placed them comfortably over 10 percent of the vote and there was even talk of the EFF overtaking the DA to become the official opposition party. But in the end, the EFF won 9.5 percent, a smaller share of the vote than in 2019, with a lower turnout.

Malema put this loss of votes down to “commendable and decisive rise of the MK party that performed above the EFF in KZN and Mpumalanga”. However, this is not the only reason why the EFF did not advance in this election. Despite the party’s very prominent campaign to register voters, even fewer people voted than in 2019. Both of these factors should prompt a serious discussion at all levels in the EFF, in order to determine the correct way forward.

Malema has described the MK Party as the “relatives” of the EFF. This is correct in the sense that both parties emerged as splits from the ANC. But this election shows that it is precisely the association with the ANC and black nationalist offshoots like the MK party that is the problem.

On the one hand the EFF was founded as a socialist alternative to the ANC, and identifies itself as a Marxist organisation, but on the other hand it retains the ambiguous class position occupied by the ANC.

In recent years, the EFF has reached out to black business leaders, to form a broad front against ‘white monopoly capital’. But if you are a black businessman in South Africa, who are you going to choose: the EFF, with its calls for socialism and the eradication of corruption, or Zuma, who is closer both socially and politically?

The bottom line is that the EFF failed to distinguish itself politically. It is a law of politics that if two parties have fundamentally the same programme, then the one with the strongest apparatus will eventually consume the other. In addition to Zuma’s own considerable resources, MK has the financial and organisational support of a section of the black bourgeoisie, of the traditional chiefs in the countryside, of the state bureaucracy, and even of the ANC itself. In a competition for ‘radical’ black nationalist wing of ANC voters, the EFF can only lose.

Worse still, by identifying itself as fundamentally the same as the ANC and MK, the EFF has been unable to reach the millions of workers and youth who have rejected the ANC, but do not yet see an alternative to vote for in parliament.

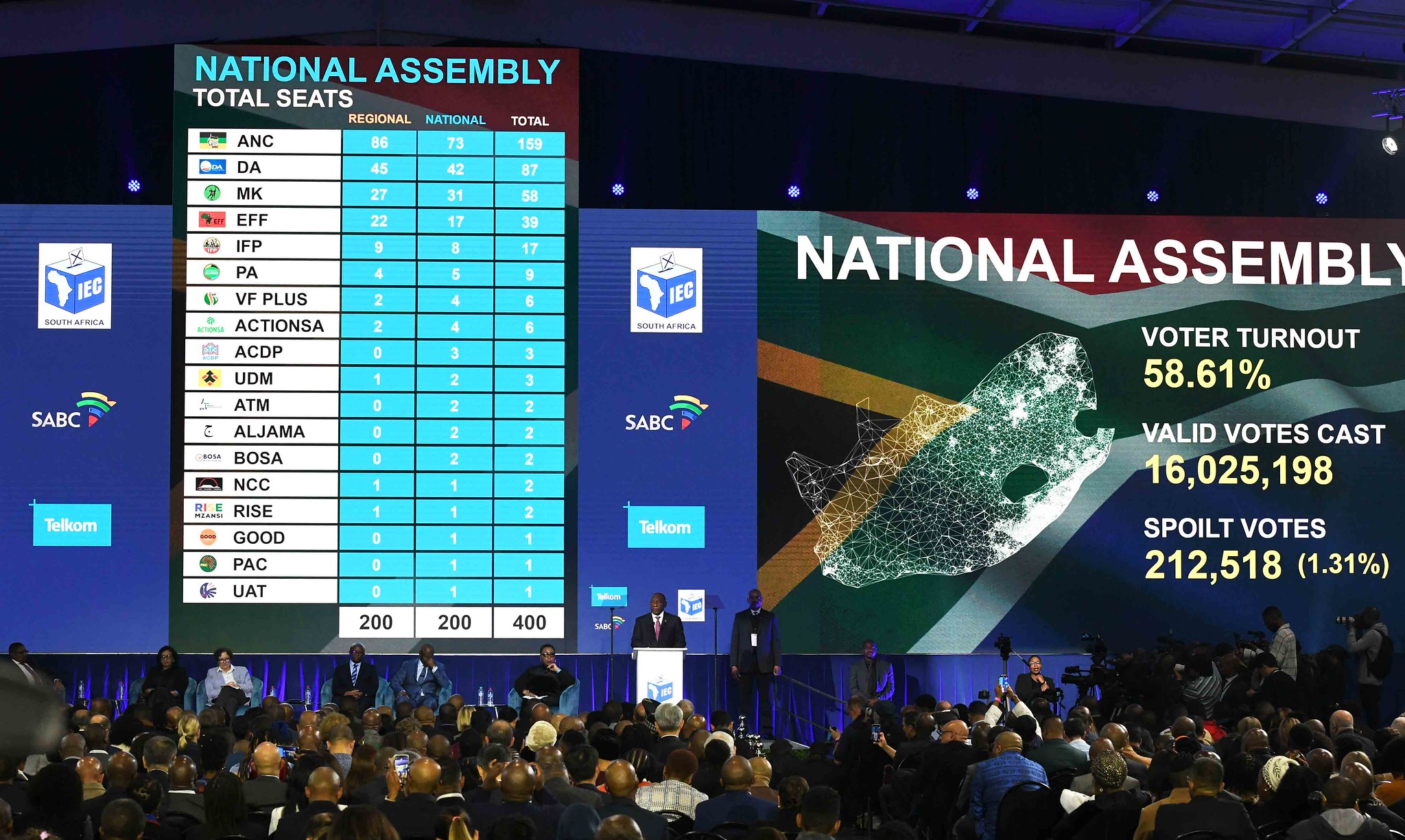

As expected, the voter turnout for the 2024 elections was the worst in South Africa’s democratic history. With a huge drive from leading political parties in the run-up to the election, and with the initial queues evident on voting day, some anticipated the turnout would increase. This was not the case, as the turnout at the polls dropped below 60 percent of registered voters. Of a voting-age population of 43 million people, only 27.7 million registered and only around 16 million actually voted.

In reality, what this election shows is a lack of enthusiasm and trust for all political parties. But that does not mean South Africans are apolitical. In recent years, the decline in voter participation has been matched by an intensification of political action, such as the Fees Must Fall movement on university campuses and bursts of predominantly wild cat strikes, which have been seen in the industrial metal sector, public healthcare sector and public education sector.

Speaking to working-class people, the story fits the statistics. When asked, a security guard working at the V&A Waterfront in Cape Town said: “I can’t really see the point in voting, but more importantly there are no good options for us (workers)”. When asked what kind of slogans would motivate his attendance at the ballot box, he answered: “We need those who claim to be socialists to act like socialists”.

It must be recognised that the strategy of behaving as the ANC painted red has failed. The way forward is clear. Only by breaking completely with the class collaborationism of the ANC and its more ‘radical’ offshoots, and standing exclusively for the interests of the working class and poor rural masses of South Africa, can the EFF become the revolutionary socialist party it aspires to be, and at last mobilise those workers and youth who are ready to fight but are looking for a clear, independent leadership.

Unstable coalitions

The ANC no longer has enough seats to form a majority government by itself, but it remains the largest party in the National Assembly. The days following the publication of the initial election result have therefore been occupied with feverish talks and backroom negotiations. But whichever arrangement the ANC manages to cobble together will produce nothing but further instability and crisis in South African politics.

The ‘moderate’, bourgeois wing of the ANC, along with most foreign investors, favours some form of coalition or agreement with the DA, backed by big capital. But for the ANC to carry out a right-wing programme in alliance with the party of white capital would not only alienate the party even further from the black majority of the country; it could easily provoke a rebellion from within the ANC itself.

In many ways, MK is the natural coalition partner for the ANC / Image: GovernmentZA, Flickr

In many ways, MK is the natural coalition partner for the ANC / Image: GovernmentZA, Flickr

In many ways, MK is the natural coalition partner for the ANC, as it is nothing other than a part of the ANC, which split away to tip the balance in favour of small black capital. This likely lies behind Zuma taking a leaf out of Donald Trump’s book, claiming election fraud, and threatening that MK MPs will refuse to take their seats in parliament: a negotiating tactic intended to use the threat of political paralysis and unrest in KZN to force concessions from the ANC.

Currently, MK are demanding that Ramaphosa be deposed from the presidency, and have made this their primary demand in relation to any potential coalition. This would essentially amount to a renewed takeover of the ANC by its ‘Zuma’ wing. For now, this has been dismissed as unacceptable by the ANC, which has therefore been forced to look further afield for coalition partners.

At the time of writing, the ANC’s National Executive Committee has publicly proposed a government of ‘national unity’. “We want to bring everybody on board,” confirmed the ANC Secretary-General, Fikile Mbalula. If you can’t form a coalition with anyone, then form one with everyone!

Such an arrangement may give the appearance of stability in the short term, but would ultimately discredit all the parties involved, and only increase the anger of the masses towards the post-1994 regime as a whole. Without a mass revolutionary party prepared to overthrow the entire corrupt establishment, demagogues like Zuma only stand to gain.

The EFF does not have enough seats to form a coalition with the ANC on its own, but could join a wider coalition with other parties, and have raised the demand that they be given the finance ministry and the speaker of the National Assembly as part of any deal. To take this course would be a potentially disastrous mistake.

As has happened many times around the world, when a left-wing party promising change enters into government with the parties of the ruling class, it becomes responsible for the crisis experienced by the masses, without any means of carrying out its own programme. In so doing, it discredits itself in the eyes of the very people it claims to represent.

Any unprincipled agreement with the ANC would effectively amount to an agreement with the South African ruling class, and can only be a trap for the EFF and for the working class.

For a revolutionary party

The economic and social crisis that has been developing in South Africa for years has finally burst onto the political plane / Image: GovernmentZA, Flickr

The economic and social crisis that has been developing in South Africa for years has finally burst onto the political plane / Image: GovernmentZA, Flickr

Any way you cut it, South Africa faces a future of even deeper instability. With this election, the economic and social crisis that has been developing in South Africa for years has finally burst onto the political plane. In the context of a global crisis of capitalism, this will mean no solution to the energy crisis, unemployment and economic stagnation.

The compromise of 1994 is breaking down. The ruling class is split and can no longer rule as in the past. The crisis is attacking both the workers and the middle class. Big swings to the left and the right are implicit in the situation.

Under the blows of the crisis, the masses will test all political parties as they try to find a way out. Blocked from finding a political solution to their problems, the workers will start to move decisively against this rotten capitalist system.

The South African working class has proud revolutionary traditions and powerful organisations. When it takes the road of revolution once more, it will rock the whole of Africa.

What is urgently needed is a revolutionary party of the working class that rejects all class collaboration and compromise, and that stands for a bold socialist programme.

Such a party must be prepared to fight side by side with the workers, provide leadership for their struggles outside of parliament, and unite them to overthrow South African capitalism in its entirety, not just redistribute the profits made on the backs of the workers.

The material for such a party exists in abundance in South Africa. A new generation is preparing to fight and turning towards communist ideas. Together we must build it.